Phill Gregson

The following extract is taken from ‘The Man Who Made Things Out of Trees’ – from the chapter about my time with Phill Gregson, one of the last wheelwrights in Britain. I took Phill several planks of sawn timber from my tree. In return, he showed me how you make a wooden wheel.

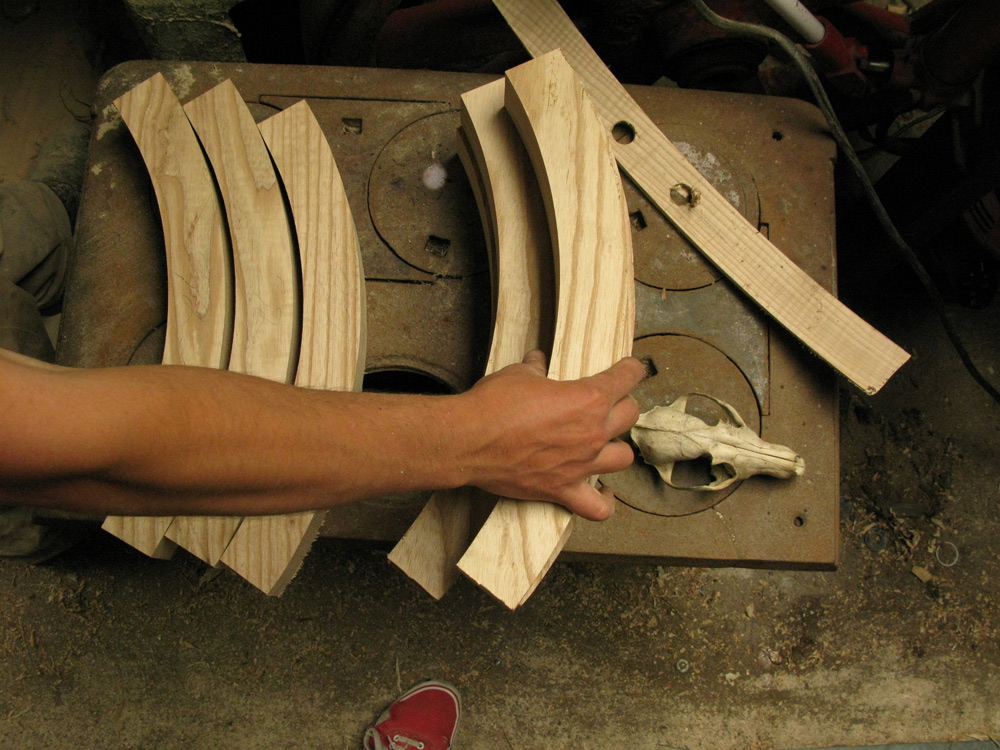

The ash felloes, which comprise the rim of the wheel, were carefully cut to the shape of the pencil markings on the band saw. With each cut a small wedge of ash dropped onto the floor at Phill’s feet. ‘There’s quite a lot of offcuts when you’re cutting out felloes, but it all gets used,’ he said. ‘There’s no such thing as waste, just expensive firewood.’

The inner face or ‘belly’ of the felloes were planed using a disc sander, to remove the saw marks. In the old days, Phill explained, the felloes would have been shaped with axes and adzes. He was taught to do everything by hand first; so if the machines fail, he can still use the hand tools. Phill worked deliberately and precisely. He measured and re-measured; he made markings in pencil, then he checked them, thickening the graphite dash he had already made, then he checked his measurements again. In every movement and act there was evidence of craftsmanship – the basic and enduring impulse to do a job well, for its own sake.

The ash felloes, which comprise the rim of the wheel, were carefully cut to the shape of the pencil markings on the band saw. With each cut a small wedge of ash dropped onto the floor at Phill’s feet. ‘There’s quite a lot of offcuts when you’re cutting out felloes, but it all gets used,’ he said. ‘There’s no such thing as waste, just expensive firewood.’

The inner face or ‘belly’ of the felloes were planed using a disc sander, to remove the saw marks. In the old days, Phill explained, the felloes would have been shaped with axes and adzes. He was taught to do everything by hand first; so if the machines fail, he can still use the hand tools. Phill worked deliberately and precisely. He measured and re-measured; he made markings in pencil, then he checked them, thickening the graphite dash he had already made, then he checked his measurements again. In every movement and act there was evidence of craftsmanship – the basic and enduring impulse to do a job well, for its own sake.

The ‘speech’ was placed face down on the wheel stool and the first felloe was marked with a bevel, for a cut to be made midway between two spokes. The next felloe was similarly marked and cut. Soon all the felloes were resting on the spokes. Phill explained that the felloes are cut with small gaps between them called ‘joints’: when the iron-tyre is fitted, the last part of the wheel building process, the felloes are drawn together to press down on the spokes. If the felloes tighten without maintaining the right degree of pressure on the spokes, the wheel is said to be ‘felloe-bound’ and it will be weaker. The felloes, marked and numbered, were ready to be bored with holes.

The more I understood about the process, the less Phill spoke. The afternoon passed in a gentle sea of timeless, elemental sounds: the rhythmical rasp of the hand planer as the wood yielded to Phill’s wishes; the ringing crack of the mallet; the scrape of Phill’s pencil on wood; the plunk of ash touching oak; the caw of the spokeshave on the felloes; and the hiss of sand paper turning dry ash to dust. The process was exhaustive and protracted: I thought of another line from The Wheelwright’s Shop – ‘Hurry being not so great then as now.’ Phill didn’t hurry. He was making a wheel for a customer and showing me the process at the same time, but he was engaged in the work for itself. The satisfaction of the wheel coming out right was the reward.

Using a tool called a spoke-dog – a three-foot long bar of ash with an iron hook on the end – Phill pressed each pair of spokes together and tapped the felloes on with a hammer. Wooden wedges, with a bit of Phill’s spit, were driven into the exposed end of the spoke tangs, to keep the wheel bound until it was hooped. The last felloe was measured, cut, drilled and fitted. Metal slips were tacked in across the felloe-joints, to keep the wheel in line. The outside or ‘sole’ of the felloes were bevelled, ready for hooping. Using an instrument called a ‘Traveller’, Phill measured the outer circumference of the wheel. He scratched a figure in pencil on the white ash, straightened his back, clasped the wheel in both hands and said: ‘We’re done.’

We wandered out of the workshop into the yard where golden sunlight was illuminating the row of wooden wheels awaiting repair.

‘It still surprises me, but I get wheels in which are 150 years old and they’re often in almost perfect condition,’ Phill said. ‘It’s only an accident or a bit of woodworm which has brought them to me. And they’ve been used regularly. In fact, if they are used regularly, they tend to be in better condition.’

‘It still surprises me, but I get wheels in which are 150 years old and they’re often in almost perfect condition,’ Phill said. ‘It’s only an accident or a bit of woodworm which has brought them to me. And they’ve been used regularly. In fact, if they are used regularly, they tend to be in better condition.’

I thought of the ash planks that I’d given Phill. In a few years, he’d get sixty or so felloes out of the timber. I wondered if the wheels he would make with my ash might be resting against a wheelwright’s shop, awaiting some minor repair, in 2170. Conceivably the life of the timber in use could be longer than the life of the ash tree. To give part of my tree such a distant end was an appealing thought. your tree.’